Sunday, February 10, 2013

UNCLE HAYATO'S TEA TALES: NAGAI DŌKYU

Monday, January 18, 2010

JAPANESE AESTHETICS: Plants in the Visual Arts (Geijutsu to Shokubutsu)

The graphic or illustrative arts in Japan traditionally have relied on the sensitivity of the artist to nature and thus, have been likely to be simple, compact, and modest, yet elegant. Traditional renderings of landscapes, for example, do not display the wide range of colors that is seen in Western oil paintings or watercolors. This same simplicity and grace applies to sculpture as well: delicately carved and small in size.

Plants, flowers and birds, or at least their outlines are frequently rendered in lifelike colors on fabric, lacquer ware and ceramics. The love of natural forms and an enthusiasm for the expression of nature in idealized style have been the key intentions in the development of traditional Japanese arts such as ikebana (flower arrangement, chanoyou (the tea ceremony), tray landscapes (bonkei), bonsai, and landscape gardening. It is through these arts that the Japanese people have attempted to incorporate the beauty of nature into their spiritual values and daily lives.

For the decoration of a teahouse, a modest flower was selected to conform with the principle that flowers should always look as if they were still in nature. The Japanese have sought to express the immensity as well as the simplicity of nature with a single wild flower in a solitary vase.Tuesday, November 10, 2009

CHA-DO: It's Not Just For Ladies Anymore!

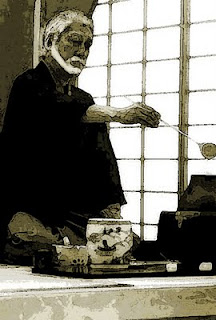

Even during the Meiji Era, the Era of Enlightened Rule, it was required, pre-marriage training for women. In the preceding Tokugawa Period, its study was encouraged among samurai and its practice the mark of a cultured gentleman. In the current Heisei Era, the time of Emperor Akihito it is becoming a much-sought out weapon in Japan’s war on stress. It is Cha-no-yu, Cha-Dō: the tea ceremony.

Throughout Japan, on any evening, and particularly on weekends, you may find Japanese men, business men, merchants, engineers, academics, gathered together in suburban tea houses, wearing kimono, hakama, and haori, to immerse themselves in traditional Japanese culture and in particular, this traditional Japanese art, as a means of shedding off the stress and strain of modern life. How? With what would be termed in the West as a “tea party.”

On any evening at the Urasenke School of Tea, one can find an ever increasing number of Japanese men studying the traditions and art of tea; indeed, on some evenings the number of male pupils (largely men over 40) outnumbers women. Japanese people, regardless of age or gender, are rediscovering the beauty and emotional calming effects of Cha-Dō, as a transcendental interlude, a time of peace and re-focusing one’s life. Numerous magazines have recently produced articles, even special “tea” editions, which were quickly sold out as Japan discovers that “new” is not always better and the old ways, tradition, can have a place of significance in the life of the modern Japanese man.

“Cha…it’s not just for ladies anymore!”

Thursday, March 12, 2009

UNCLE HAYTO'S TEA TALES

According to tradition, Myōei Shonin[1]of Toga-no-ō received some tea plants from Eisai Shōnin[2] and planted them there. To this day, both connoisseurs of tea and devotees of sadō (the Way of Tea) consider this tea to be the absolute best, largely because Shonin himself used it. He once wrote down what he considered to the, as he called them, the Ten Virtues of Tea:

1. Has the blessing of all the Gods.

2. Promotes filial piety.

3. Drives away the Devil.

4. Drives away drowsiness.

5. Keeps the Five Viscera[3] in harmony.

6. Fights off disease.

7. Strengthens friendships.

8. Disciplines the mind and body.

9. Calms the passions.

10. Gives a peaceful death.

[1] Myōei Shonin is credited with being the first actual tea manufacture in Japan.

[2] Eisai (1141 – 1215) was a Zen Buddhist monk. A bit of a renegade of the Tendai Buddhist School, he took up the Rinzai school of Zen and after studying in China, brought the discipline to Kyoto and Kyushu. This drew heavy criticism from the Tendai leaders and Eisai found himself charged with heresy. In 1199 he fled to Kamakura were Hōjō Masako took him under his protection and made him abbot of Kennin-ji Temple.

[3] The internal organs in a human body can be classified into five viscera organs (Wu Zang) and six bowel organs (Liu Fu). The five zang organs are: heart, liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys. The six fu organs are: stomach, small intestine, large intestine, gallbladder, urinary bladder and Triple Energizer (San Jiao).

Thursday, March 5, 2009

UNCLE HAYATO'S TEA TALES

Founder Of The Tea Ceremony

Shuko’s real name was Murata Mōkichi and he was the son of Moku-ichi Kenko of Nara. Even as a young man he had a taste for, if not an appreciation of, tea and an obsession with gambling at tocha, tea-tasting tournaments. Shuko, with a number of his friends and other delinquents, would gather at some nearby inn or roadhouse where they would hold impromptu parties and drink large amounts of tea, competing to see who could identify the “true” tea from Uji, a village on the southern outskirts of Kyoto, and which was not. These parties were often wild, decadent affairs where large sums of money or lavish prizes would go to the winners. Needless to say, this was not what his family had intended for him.

His addiction to tocha eventually was so out of hand that his family sent him away to the priesthood at the Shōmei-ji monastery where he lived for almost ten years. But being that he was young and lazy, he was eventually expelled from the temple. From there he journeyed to Kyoto where he entered the Daitoku-ji at Murasakino, where he studied under Ikkyu Sōjun[i]. His one great fault was that he would always fall asleep in the daytime (as well as nighttime) to the detriment of his studies and the amusement of his fellow students. Some clever fellow even went so far as to remark that if his teacher was Ikkyu (one slumber) then the Shuko should be called Hyakkyu (a hundred slumbers).

That he was a source of entertainment to his fellows and that his studies were indeed suffering did not go unnoticed by Shuko. He went so far as to go to a doctor to ask for a prescription to keep him awake so that he could study. The doctor, after listening to Shuko’s sad tale, suggested that tea was the best stimulant for the mind and told the hapless student to drink lots of it - and often. He took up drinking the tea of Toga-no-ō[ii] and found it very effective indeed. Soon he was not only drinking the tea by himself but whenever anyone came to see him he would offer them some as well, accompanied by considerable ceremony.

By some way or means, the Shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, heard of this and took an immediate interest; in fact, he was so interested that he summoned Shuko to the palace and ordered him to arrange a ceremony for drinking tea. Assisted by two friends, Nō-ami[iii] and Sō-ami[iv], Shuko compared the tea etiquettes already in use and selected parts from several to use. Yoshimasa was quite pleased by the young man’s efforts. He instructed Shuko to give up the monastic life and to build a hut for himself near Sanjo. The Shōgun also gave him a plaque, written in his own hand to be placed over the gate, which read Shu-kō-an-shu or “Pearl-Bright-Cell-Master.”

From then on, Shuko devoted himself only to the arts of cooking special meals, eating them, infusing tea and of course drinking it. He also took to entertaining his friends with these special meals, and of course preparing tea. In time at such gatherings, he and his friends started to entertain themselves by composing and reciting Japanese verses. Anyone who was anyone competed for the honor of his friendship and thus, cha or tea, began to increase in popularity.

Shuko was the first in Japan to whom the title of Tea Master was ever given. He died and the ripe age of eighty-one on the fifteenth of May in 1503 and was buried at the Shinju-an of the temple of Diatoku-ji at Murasakino in Kyoto, where he had been a student. To say that he was sorely missed would be an understatement; for after his departure, it did not take long for his friends and associates to realize that the quality of his “tea meetings” did not stem from the utensils he used or the pictures and writings on the walls but instead came directly from him and that, could never be replaced.

[i] Ikkyu Sōjun (1394-1481) was an eccentric, nonconformist Japanese Zen Buddhist priest and poet. He had a great impact on the infusion of Japanese art and literature with Zen attitudes and ideals. He also had a strong influence on the development of the formal Japanese tea ceremony.

[ii] Toga-no-ō was the first place that tea was grown in Kyoto, which was designated as real tea verses the other places where it was grown in Japan. Yosai brought tea seeds and the processing technique from China along with Renzai Zen in about 1192 A.D. He gave some seeds to his disciples who planted them at Toga no O, at his temple Kozan-ji. Thus, Toga no O is considered the starting place for tea, followed by Uji.)

[iii] Nō-ami (Nakao Shinnō) (1397 – 1494) was a poet, painter, art critic, and the first non-priest who painted in the suiboku (water-ink) style of the Chinese. He was also the grandfather of Sō-ami.

[iv] Sō-ami (1472 – 1525) was a true renaissance man of the Muromachi Period of Japanese history. He was a painter, art critic, pot, landscape gardener, and master of the tea ceremony, incense ceremony and flower arrangement, and a leading figure in the development of Japanese aesthetics.