Sunday, September 1, 2013

Saturday, June 22, 2013

SIMPLE LIVING, PART I

Sunday, February 10, 2013

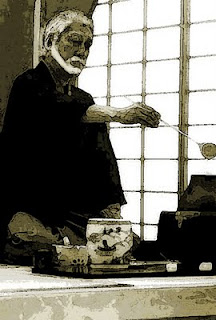

UNCLE HAYATO'S TEA TALES: NAGAI DŌKYU

Tuesday, January 22, 2013

PENNIES

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

SPECK OF LIGHT

Sunday, May 9, 2010

JAPANESE AESTHETICS: FURYU

Fūryū (風流)

The Japanese aesthetic Fūryū (風流) was derived from the Chinese word fengliu, which literally translated meant “good deportment” or “manners. After its “importation” to Japan in the eight century, the word came to refer more directly to the refined tastes of a cultivated person and to things what were associated with such people. When applied in a more aesthetic sense, the word fūryū took on a reference to the refined, even elegant behavior of an sophisticated person. As time went on, the word was applied to all things that were regarded as elegant, sophisticated, stylish, or artistic.

By the twelfth century, with the evolution of semantics in Japan, fūryū began to evolve into two distinct variations. The first variation applied fūryū to more earthy, ostentatious beauty as marked in popular art forms. In the second variation, people attempted to find fūryū in the beauty portrayed in landscape gardens, flower arrangements, architecture, and poetry about nature, normally written in classic Chinese. It was this second “branch” of fūryū that in part gave birth to cha-no-yu or the tea ceremony, during the Muromachi Jidai or Muromachi Era (1333- 1573).

During the Edo Period or Edo Jidai (1603 – 1868), a form of popular fūryū became evident through a style of fictional prose known as ukyo-zōshi.[i] A second popular interpretation of fūryū became apparent in such art forms as haikai[ii] poetry and the nanga[iii] style of painting; an interpretation that advocated a withdrawal from all of life’s burdens. An example of this version of fūryū may be found in the following poem by Bashō :

the beginning of fūryū

this rice planting

song of the north.

A more contemporary interpretation of fūryū, strongly influenced by Zen, lies in the two characters which comprise the term, 風流, wind and flowing. Just like the moving wind, fūryū can only be sensed: it cannot be seen. Fūryū is tangible yet at the same time, intangible in the elegance which it implies; moreover, just like the wind, fūryū puts forward a wordless, transitory beauty, which can be experienced only in the moment: in the next it is gone. Interestingly, several styles of folk dances, yayako odori and kaka odori, have come to be referred to as fūryū or “drifting on the wind” dances and are quite popular.

[i] Ukiyo-zōshi (浮世草子 ) or “books of the floating world” was the first major genus of popular Japanese fiction, by and large written between 1690 and 1770, primarily in Kyōto and Ōsaka. Ukiyo-zōshi style literature developed from kana-zōshi (仮名草子 ) [a type of printed Japanese book that was produced largely in Kyōto between 1600 and 1680, referring to books written in kana rather than kanji]. Indeed, ukiyo-zōshi was originally classified as kana-zōshi. The actual term ukiyo-zōshi first appeared around 1710, used in reference to romantic or erotic works; however, later the term came to refer to literature that included a diversity of subjects and aspects of life during the Edo Jidai. Life of a Sensuous Man, by Ihara Saikaku, is regarded as the first work of this type. The book, as well as other passionate literature, took its subject matter from writings of or about courtesans and guides to the pleasure quarters. Although Ihara’s works were not considered “high literature” at the time, they became extremely popular and were crucial to the further development and broadened appeal of the genre. After the 1770s, the style began to stagnate and to slowly decline.

[ii] Haikai (俳諧 , meaning comic or unorthodox) is short for haikai no renga, a popular style of Japanese linked verse that originate in the sixteenth century. Unlike the more aristocratic renga, haikai was regarded as a low style of linked verse intended primarily for the average person, the traveler, and for those who lived a less privileged lifestyle.

[iii] Nanga (南画 , or southern painting) also known and bunjinga (文人画 ) , intellectual painting) was a somewhat undefined school of Japanese painting which thrived during the late Edo Period. Its artists tended to regard themselves as an intellectual elite or literati. The artists who followed this school were both unique and independent; yet they all shared a high regard for traditional Chinese culture. Their paintings, most often rendered in black ink, but at times with light color, were inclined to represent Chinese landscapes or related subjects, much in the same form as Chinese wenrenhua or literati painting of the nanzonghua or Chinese “southern school” or art.

Copyright 2010 by Hayato Tokugawa and Shisei-Do Publications. All rights reserved.

Sunday, March 7, 2010

KINDNESSES UNEXPECTED

Kindnesses Unexpected

In 1891, Lafcadio Hearn made a voyage to the Oki Islands or Oki-shotō (隠岐諸島), a group of volcanic, one hundred miles west off the western coast from Izumo and Shimane Prefecture. As he put it, “Not even a missionary had ever been to Oki, and its shores had never been seen by European eyes, except on those rare occasions when men-of-war steamed by them, cruising about the Japanese Sea.” It was here that he experienced some not-so-small kindesses and surprises.

“On the morning of the day after my arrival at Saito, a young physician called to see me, and requested me to dine with him at his house. He explained very frankly that, as I was the first foreigner who had ever stopped in Saigo, it would bring much pleasure both to his family and to himself to have a good chance to see me; however, the natural courtesy of the man overcame any hesitation I might have felt to gratify the curiosity of strangers. I was not only treated delightfully at his beautiful home, but actually sent away with presents; most of which I attempted, in vain, to decline. In one matter, however, I remained obstinate, even at the risk of offending: the gift of a wonderful specimen of bateiseki (a substance which I shall speak of later). This I persisted in refusing to take, knowing it to be not only very costly, but very rare. My host at last yielded; but afterwards, secretly sent two smaller specimens to the hotel, which Japanese etiquette made it impossible to return. Before leaving Saigo, I experienced many other unexpected kindnesses from the same gentleman.

“Not long after, one of the teachers of the Saigo public school paid me a visit. He had heard of my interest in Oki, and brought with him two fine maps of the islands made by him, a little book about Saigo, and as a gift, a collection of Oki butterflies and insects that he had also made. It is only in Japan that one is likely to meet with these wonderful exhibitions of pure goodness on the part of perfect strangers.

“A third visitor, who had called to see my friend, performed an act equally characteristic, but which also pained me. We squatted down to smoke together. He drew from his obi a remarkably beautiful tobacco pouch and pipe case, containing a little silver pipe, which he began to smoke. The pipe case was made of a sort of black coral, curiously carved, and attached to the tabako-iré, or pouch, by a heavy cord of three colors of braided silk, passed through a ball of transparent agate. Seeing me admire it, he suddenly drew a knife from his sleeve, and before I could stop him, severed the pipe case from the pouch and presented it to me. I felt almost as if he had cut one of his own nerves apart when he cut that wonderful cord; and nevertheless, once this had been done, to refuse the gift would have been rude in the extreme. I made him accept a present in return; but after that experience, I was careful never again, while in Oki, to admire anything in the presence of its owner.”

Even now in the 21st century, if one will take the time to meet people, and to experience the true Japan, he too is bound to experience such amazing kindness, which seems so lacking elsewhere in the world.

*Print by Mishima Shoso (1856 - 1926) titled Sparrow Grand-pa (c. 1900) illustrating a Japanese folktale about an honorable old man who rescued a sparrow (suzume). Later, he was invited to the village of sparrows and given a box of gifts.

Monday, January 18, 2010

JAPANESE AESTHETICS: Plants in the Visual Arts (Geijutsu to Shokubutsu)

The graphic or illustrative arts in Japan traditionally have relied on the sensitivity of the artist to nature and thus, have been likely to be simple, compact, and modest, yet elegant. Traditional renderings of landscapes, for example, do not display the wide range of colors that is seen in Western oil paintings or watercolors. This same simplicity and grace applies to sculpture as well: delicately carved and small in size.

Plants, flowers and birds, or at least their outlines are frequently rendered in lifelike colors on fabric, lacquer ware and ceramics. The love of natural forms and an enthusiasm for the expression of nature in idealized style have been the key intentions in the development of traditional Japanese arts such as ikebana (flower arrangement, chanoyou (the tea ceremony), tray landscapes (bonkei), bonsai, and landscape gardening. It is through these arts that the Japanese people have attempted to incorporate the beauty of nature into their spiritual values and daily lives.

For the decoration of a teahouse, a modest flower was selected to conform with the principle that flowers should always look as if they were still in nature. The Japanese have sought to express the immensity as well as the simplicity of nature with a single wild flower in a solitary vase.Tuesday, November 10, 2009

CHA-DO: It's Not Just For Ladies Anymore!

Even during the Meiji Era, the Era of Enlightened Rule, it was required, pre-marriage training for women. In the preceding Tokugawa Period, its study was encouraged among samurai and its practice the mark of a cultured gentleman. In the current Heisei Era, the time of Emperor Akihito it is becoming a much-sought out weapon in Japan’s war on stress. It is Cha-no-yu, Cha-Dō: the tea ceremony.

Throughout Japan, on any evening, and particularly on weekends, you may find Japanese men, business men, merchants, engineers, academics, gathered together in suburban tea houses, wearing kimono, hakama, and haori, to immerse themselves in traditional Japanese culture and in particular, this traditional Japanese art, as a means of shedding off the stress and strain of modern life. How? With what would be termed in the West as a “tea party.”

On any evening at the Urasenke School of Tea, one can find an ever increasing number of Japanese men studying the traditions and art of tea; indeed, on some evenings the number of male pupils (largely men over 40) outnumbers women. Japanese people, regardless of age or gender, are rediscovering the beauty and emotional calming effects of Cha-Dō, as a transcendental interlude, a time of peace and re-focusing one’s life. Numerous magazines have recently produced articles, even special “tea” editions, which were quickly sold out as Japan discovers that “new” is not always better and the old ways, tradition, can have a place of significance in the life of the modern Japanese man.

“Cha…it’s not just for ladies anymore!”

Friday, October 30, 2009

ON SIMPLICITY

I believe in simplicity; yet, it is surprising as well as distressing, how many inconsequential concerns even the wisest man thinks that he must focus on in a single day – how rare the matter that he thinks that he must pass over. When a man of science or mathematics wishes to solve a difficult problem, the first step would be to clear the equation of all impediments and distractions, all unnecessary data; thus reducing it to its most simple terms. We should do the same: simply the problems of life and distinguish what is actually necessary and real.

One should search within himself to see where ones actual roots lie.

Friday, October 16, 2009

JAPANESE AESTHETICS (Bigaku)

JAPANESE AESTHETICS (Bigaku)

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of traditional Japanese aesthetic thought is the tendency to attach far greater value to symbolic depiction than realistic portrayals. Another attribute to be considered is the supposition that in order to be true art, a work has to involve a discerning representation of what is beautiful and an aversion from the crude and profane. As a result, artists have traditionally tended to select nature as their subject matter, steering clear of depictions of everyday, common life.

It was the Heian court, often described as having an exaggerated taste for grace and refinement, which exerted an enduring impact on subsequent cultural traditions, designating elegance as a key measure of beauty. Numerous cultural and artistic concepts, such as okashi, fūryū, yūgen, and iki carry with them a nuance of elegance.[1]

Another quality, one to which great value is attached, is impermanence or transience, itself a variation of elegance; exquisite beauty being regarded as both fragile and transitory. Metaphysical profoundness was provided through a merging of Buddhism, with its emphasis on the inconsistency and uncertainty of life, with this ideal. Numerous aesthetic conventions, such as wabi, sabi, yūgen and aware (with its subsequent amplification of mono no aware) all imply transience.

Over time, the presence of an artistically created void, in either time or space, became an important concept in aesthetic theory. The concept of simplicity became a culmination of the concepts of simulation and substitution, which stressed symbolic representation. Aesthetic concepts such as wabi, sabi, ma, shibui and yojō[2] are all inclined toward simplicity in terms of their basic inferences, consistently demonstrating distaste for elaborate beauty.

Simplicity denotes a certain naturalness or lack of pretense. In traditional Japanese aesthetics then, the separation between art and nature is considerably smaller than in Western art, stemming from the belief that the mysteries of nature cannot be presented through portrayal, but only suggested and the more succinct the suggestion, the more effective it becomes.

[1] The aesthetic concepts of wabi, sabi, yūgen, aware and mono no aware will be discussed in subsequent articles.

[2] The aesthetic concepts of ma, shibui, and yojō will be discussed in subsequent articles.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Emotions and Forms: Uniquely Japanese

Emotions and Forms: Uniquely Japanese

Much of my formal education and training had been in science and law; both disciplines based upon logic. As I grew older, and hopefully wiser, and as a student of traditional Japanese Budō and Bushidō, I began to read and study about the Japan of past days; and as I experienced life in Japan, not only in the dojo but in the small towns and villages, away from the cities, I began to think about such Japanese things as jōcho (emotion) and katachi (forms of behavior). People took tradition seriously. They often enjoyed dressing in kimono; they enjoyed eating together as a family, gathered around a low table in the living area of a simple home. People who were too loud or boisterous were given a cold shoulder. I witnessed Japanese unspoken communication and personality projection. Away from the cities, the national character was entirely different. Customs and traditions, sincerity and humor, were considered of much greater value than the logic I had learned and trained in at school. Of course there were some people who clamored for “more”, “more is better”, “modern is better”; yet, those who shouted for more reform to the modern ways, were discreetly criticized by the elders as “lacking a proper sense of humor.”

I began to realize that, yes indeed, logic had its place, but aesthetics, emotions and forms of behavior could be equally important if not more; things uniquely Japanese. When I mention “aesthetics,” I am speaking of such things as nihonjin no shizenkan, the concept of nature. When I say “emotion,” I am not speaking feelings such as joy, anger, sympathy, sadness or happiness, which we learn about in school and which we all experience naturally; I am refereeing instead to emotions that are cultivated through cultural experience; such emotions as natsukashisa, a sense of yearning for the lost, an mono no aware, an awareness of the pathos of things. By “forms,” I mean the code of conduct that has been with us for centuries, derived from Bushidō, the samurai code of ethics.

When considered together, these are the things that make Japan and the Japanese special, unique in the world. Just as Nitobé Inazo pointed out that Bushidō was the foundation of Japan’s national character, so also are these others. Even as far back as the Meiji Restoration, both emotions and forms of behavior began to go into a gradual, imperceptible decline. The rate of decline was accelerated in the Showa Era and sustained extensive deterioration after World War II, as the country suffered from Americanization and free market principles which reached deep into the Japanese heart to exert their influence on Japanese society, culture and its character as a nation. Even the Japanese educational system, has served to erode the Japanese pride and confidence in their country, largely at the hands of revisionist politicians and historians. People, particularly in the cities began to forget those things that were the country’s traditional emotions and forms of behavior, the things that should have given them the pride to be uniquely Japanese. Instead, the country falls prey to the logic and reasoning of the West and the decline continues through a process of globalization, which is nothing more than an attempt at making the world homogenous. Japan must find the means to realize and preserve its individuality and to recapture its simplicity in living, its emotions, and its forms; thus, remaining forever, uniquely Japan.

Monday, September 7, 2009

Ten Kinds of Simplicity

Ten Kinds of Simplicity

Although the attraction toward more simple ways of living a strong for some, the attraction for the opposite can be equally as strong for others. It would seem that many people are not giving even cursory consideration to more simplicity in their lives because they see it as too great a sacrifice. Instead, they seek deeper resources of satisfaction that they perceive can be found in a consumerist life-style, one which in the long-term brings higher stress and fewer true rewards. In Japan until the recent recession, the percentage of the population reporting that they were very happy remained relatively unchanged: roughly 33%. At the same time however, divorce rates doubled and suicides have tripled. An entire generation tasted the fruits of an affluent society and is now discovering that money does not buy happiness. The present recession presents a special opportunity to take a new course in one’s life: to pull back from the rat race and move into a life that is, although materially more modest, rich with family, friends, community, creativity, and service.

To present a more realistic representation of the extent and expression of a simpler life-style for today’s complex society, here are ten different approaches to consider. Although they may overlap a bit, each expression of simplicity seems distinct enough to merit a separate category.

Simplicity by Choice

Simplicity means choosing a path through life consciously, deliberately and as a matter of one’s own choice. As a path or “way” that places emphasis on freedom, the choice of simplicity also means staying focused and not being distracted by the consumer culture. It means consciously organizing one’s life so that they can give their true personal gifts to the world: the essence of ourselves.

Commercial Simplicity

A more simplistic life would mean that there is then a more rapidly growing personal market for healthy and sustainable products and services of all kinds; from home design, building materials and energy systems to food. There exists the potential for an enormous expansion of conscious economic activity toward sustainability.

Compassionate Simplicity

With simplicity in one’s life can come a kinship, a bond with the community and a desire for reconciliation, even with other species as well as a strong desire to be of true service to others and a stronger desire for cooperation and fairness, which seeks a future which is beneficial to all and decreases the gap rich and poor.

Ecological Simplicity

Simplicity mans to choose ways of living that tread far more lightly on the earth, reducing one’s “ecological footprint.” An ecological simplicity brings with it a deep interconnection with all life and a consciousness of threats to its well-being (such as climate change, species extinction and resource depletion) coupled with a desire to do something about it. Ecological simplicity cultivates a type of “natural capitalism:” economic practices that value the importance of natural ecosystems and which can impact the community in terms of its health and productivity.

Elegant Simplicity

Simplicity can mean that the way one lives their life represents a work of unfolding artistry. It is an understated aesthetic that contrasts with the excess of consumerist lifestyles. Drawing on the influence of Zen, Confucianism, and Taoism, it celebrates natural materials and clean, functional expressions of simplicity found in the hand-made arts and crafts from the community.

Frugal Simplicity

By cutting back on spending that is not truly serving one’s life, and by practicing skillful management of one’s personal finances, one can achieve greater financial independence. Frugality and careful financial management bring increased financial freedom and the opportunity to more consciously choose one’s path through life. Living with less also decreases the impact of our consumption on the earth and frees resources for others.

Natural Simplicity

Simplicity in one’s life can signify a remembrance and reconnection to one’s deep roots in the natural world. It means to experience one’s connection with the ecology of life in which one lives and to balance their experience of the man-made environments with time in nature. It means to celebrate the experience of living through the seasons.

Political Simplicity

Simplicity means to organize one’s life in ways that enable people to life more lightly and sustainability, which in turn, involves changes to the life of the community: from transportation and education to the design of our homes, town, and workplaces. Such can also be a media politic because mass media can be the primary way to reinforce or transform the community’s awareness of consumerism. Political simplicity is a politic of conversations within the community that builds local, face-to-face connections: networks of relationships, which enable others to make conscious decisions about change in their lives as well.

Spiritual Simplicity

One may approach life as a meditation and cultivate their experience of intimate connections with all that exits around us: plants, animals, friends, and neighbors. Spiritual simplicity is more concerned with consciously enjoying life in its unadorned richness rather than with any particular standard or manner of material living. By cultivating a spiritual connection with life, one tends to look beyond surface appearances and to bring their inner self into relationships of all kinds.

Uncluttered Simplicity

To live an uncluttered life means to take charge of a life that is too busy, too stressed and too fragmented. It means cutting back on inconsequential distractions and focusing on the essentials, whatever those may be for each unique life.

Thursday, September 3, 2009

SIMPLE LIVING

We live in a fast paced, consumer oriented society; indeed, we are constantly under pressure to consume. The mantras of the 21st century are: “More is better” and “New is better.” We are bombarded, twenty-four hours a day, by advertisements that tell us we are less than successful if we don’t own the latest luxury Lexus, or the 50-inch plasma TV and home entertainment center. We are told that we are less than acceptable if we do not possess and wear the latest designer fashions, the newest make-up, or don’t eat in the trendiest new restaurants. We need bigger and better computers, video games, cell phones capable of texting around the world, taking photographs, videos, playing games, and keeping us constantly on the Internet. All these things are wonders to behold, the best our technology can give us – for now. In two year, a year, six months, some of our “cool stuff” will be totally outmoded, obsolete. What are we told we must do, in order to be successful? We need to discard what is outmoded and replace it with what is now “new and improved.”

So we spend what we earn, and then we spend what we don’t have but will earn – maybe. We owe on our homes, our cars, our appliances, and our futures. We suddenly wake up to find that we have mortgaged our entire lives; and for what? Are we happier? Do we now have peace of mind? Are we more secure in our lives? Probably not!

To quote Confucius: Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated. How true! Amatai-no-Shugo-Ryū offers a simple tenet, in line with Wa-Dō, by which one is able to change the course of their personal consumerism, to in effect, get off the “consumerist merry-go-round.” The principle is itself simple, so simple in fact, that for our intents and purposes, it is referred to as “simple living.”

One may also refer to the principle as “voluntary simplicity,” although, simple living sounds better. It is a lifestyle which is distinguished by minimizing the modern ethic of contemporary “more-is-better” pursuit of wealth and consumption. Advocates of simple living may chose to do so for a variety of personal reasons such as: spirituality, health, increase in “quality time” for family and friends, stress reduction, personal taste or frugality. Other people may allude to more socio-political goals that are aligned with other anti-consumerist movements, including conservation, social justice and sustainable development. All worthy causes and reasons in of themselves to simplify one’s life. One can describe voluntary simplicity as a manner of living that is outwardly more simple and inwardly more rich: a way of being in which our true and active self is brought into the light of our consciousness and applied to how we life as individuals and as members of a community or society.

Simple living is a concept far different from those living in forced poverty. It is a voluntary choice of lifestyle. Although asceticism generally encourages living simply and refraining from luxury and indulgence, not all supporters or parishioners of voluntary simplicity are ascetics.

The recorded history of simple living can be found in the teachings of Taoism, of Confucioius and Mencius. Buddha was an ascetic. In Japan we find a strong advocacy for simple living in the teachings of Zen Buddhism and Bushidō, which made the ways and means of simple living something distinctly Japanese.

Some people practice simple living to reduce the need for purchased goods or services and by doing so, reduce their need to, in effect, sell their time for money. Some will spend the extra free time helping family and friends. During the holiday seasons, such people often perform forms of alternative giving, such as volunteer work with the poor and homeless. Others may spend the extra free time to improve the quality of their lives by, for example, pursuing creative activities such as sadō, shodō, or studying a martial art.

One approach to adapting a more simplified way of living is to focus more fundamentally on the underlying reasons and motivation of buying and consuming so many resources for what we are led to believe is a good quality of life. Modern society tells us that me must, in essence, buy happiness; however, materialism and consumerism frequently fails to satisfy us and in the long-term, may even increase the level of stress in our lives. It has been said “the making of money and the accumulation of things should not smother the purity of the soul, the life of the mind, the cohesion of the family, or the good of society.” Quite simply, the more money we spend, the more time we have to be out there earning it and the less time we have to spend with the ones we love.

Some simple suggestions to help simplify our style of living are:

Stop buying things that are not necessary. Yes we may feel having a television is important; indeed it really seems to be a necessity these days. The question is do we need the 50-inch home entertainment center or is there something lesser, which does the job just as well. If our neighbors the Yamadas buy a new TV, do we need to buy the same one or a little better? If our boss at work buys a new car, do we need to cast aside our car and mortgage our lives more to buy the same car, or one just a little bit better? Probably not. One should buy what they need: what gets the job done and not necessarily anything more than that.

Throw away, or better donate to someone in need, what you, yourself don’t need.

Focus on what is truly important.

Listen to the voice within you and pay attention to it.

Obtain what you really do need (food, shelter, company). It’s nice, it’s great to have “stuff”, but perhaps we should think about what is really needed as to what we are told we want.

Keep a sense of perspective and humor about what you see and hear.

Keep in touch with your friends and family.

Don’t try to keep up with everyone else, especially because you are told you have to.

Have fun.

Grow as a person

Remember, everything will be alright!

Thursday, March 5, 2009

UNCLE HAYATO'S TEA TALES

Founder Of The Tea Ceremony

Shuko’s real name was Murata Mōkichi and he was the son of Moku-ichi Kenko of Nara. Even as a young man he had a taste for, if not an appreciation of, tea and an obsession with gambling at tocha, tea-tasting tournaments. Shuko, with a number of his friends and other delinquents, would gather at some nearby inn or roadhouse where they would hold impromptu parties and drink large amounts of tea, competing to see who could identify the “true” tea from Uji, a village on the southern outskirts of Kyoto, and which was not. These parties were often wild, decadent affairs where large sums of money or lavish prizes would go to the winners. Needless to say, this was not what his family had intended for him.

His addiction to tocha eventually was so out of hand that his family sent him away to the priesthood at the Shōmei-ji monastery where he lived for almost ten years. But being that he was young and lazy, he was eventually expelled from the temple. From there he journeyed to Kyoto where he entered the Daitoku-ji at Murasakino, where he studied under Ikkyu Sōjun[i]. His one great fault was that he would always fall asleep in the daytime (as well as nighttime) to the detriment of his studies and the amusement of his fellow students. Some clever fellow even went so far as to remark that if his teacher was Ikkyu (one slumber) then the Shuko should be called Hyakkyu (a hundred slumbers).

That he was a source of entertainment to his fellows and that his studies were indeed suffering did not go unnoticed by Shuko. He went so far as to go to a doctor to ask for a prescription to keep him awake so that he could study. The doctor, after listening to Shuko’s sad tale, suggested that tea was the best stimulant for the mind and told the hapless student to drink lots of it - and often. He took up drinking the tea of Toga-no-ō[ii] and found it very effective indeed. Soon he was not only drinking the tea by himself but whenever anyone came to see him he would offer them some as well, accompanied by considerable ceremony.

By some way or means, the Shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, heard of this and took an immediate interest; in fact, he was so interested that he summoned Shuko to the palace and ordered him to arrange a ceremony for drinking tea. Assisted by two friends, Nō-ami[iii] and Sō-ami[iv], Shuko compared the tea etiquettes already in use and selected parts from several to use. Yoshimasa was quite pleased by the young man’s efforts. He instructed Shuko to give up the monastic life and to build a hut for himself near Sanjo. The Shōgun also gave him a plaque, written in his own hand to be placed over the gate, which read Shu-kō-an-shu or “Pearl-Bright-Cell-Master.”

From then on, Shuko devoted himself only to the arts of cooking special meals, eating them, infusing tea and of course drinking it. He also took to entertaining his friends with these special meals, and of course preparing tea. In time at such gatherings, he and his friends started to entertain themselves by composing and reciting Japanese verses. Anyone who was anyone competed for the honor of his friendship and thus, cha or tea, began to increase in popularity.

Shuko was the first in Japan to whom the title of Tea Master was ever given. He died and the ripe age of eighty-one on the fifteenth of May in 1503 and was buried at the Shinju-an of the temple of Diatoku-ji at Murasakino in Kyoto, where he had been a student. To say that he was sorely missed would be an understatement; for after his departure, it did not take long for his friends and associates to realize that the quality of his “tea meetings” did not stem from the utensils he used or the pictures and writings on the walls but instead came directly from him and that, could never be replaced.

[i] Ikkyu Sōjun (1394-1481) was an eccentric, nonconformist Japanese Zen Buddhist priest and poet. He had a great impact on the infusion of Japanese art and literature with Zen attitudes and ideals. He also had a strong influence on the development of the formal Japanese tea ceremony.

[ii] Toga-no-ō was the first place that tea was grown in Kyoto, which was designated as real tea verses the other places where it was grown in Japan. Yosai brought tea seeds and the processing technique from China along with Renzai Zen in about 1192 A.D. He gave some seeds to his disciples who planted them at Toga no O, at his temple Kozan-ji. Thus, Toga no O is considered the starting place for tea, followed by Uji.)

[iii] Nō-ami (Nakao Shinnō) (1397 – 1494) was a poet, painter, art critic, and the first non-priest who painted in the suiboku (water-ink) style of the Chinese. He was also the grandfather of Sō-ami.

[iv] Sō-ami (1472 – 1525) was a true renaissance man of the Muromachi Period of Japanese history. He was a painter, art critic, pot, landscape gardener, and master of the tea ceremony, incense ceremony and flower arrangement, and a leading figure in the development of Japanese aesthetics.