Sunday, September 1, 2013

ELEPHANT ROCKS II

KUMANO SHRINE: Kwaidan

“I should like, when my time comes, to be laid away in some Buddhist graveyard of the ancient kind, so that my ghostly company should be ancient, caring nothing for the fashions and the changes and disintegrations of Meiji.”

KUMANO SHRINE: Ceiling Art

Thursday, August 18, 2011

AZUMINO WALK: A Haiku

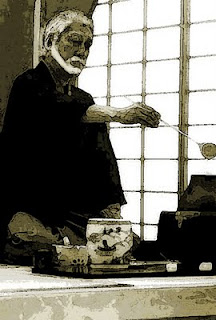

UNCLE HAYATO'S TEA TALES

Shiba kokan, whom you perhaps know as an artist and printmaker of some renown, possessed a no lesser attribute, although perhaps not so widely known, that being his ability in the art of crafting with words. For example:

One branch full-laden

With thy blossoms I must own

O flow’ring plum tree.

Now, there is a story behind this lovely verse, which has very little to do with tea at all, but which I think you will find most entertaining:

Long ago, there was a man named Mine Genwa, who happened to be the tea master to the lord of Izumo. One day, as he was walking through the countryside, as was his habit, he came upon a most beautiful plum tree, in full bloom, growing in the garden of a local farmer. Because he was a man of some sensitivity, as you might expect, he decided to stop there for quite a while in front of it, enjoying its beauty and fragrance. After a while, he said to the famer, “I would like to buy this tree.” A bit surprised, and perhaps also a bit amused, the famer at first refused to sell it, but in the end, when Genwa had offered him a very large sum, he at last relented.

With the deal concluded, Genwa departed, but early the next morning, he was back again, this time with food and sake, and proceeded to sit down and enjoy himself under the plum tree he had purchased. While he was enjoying his repast, the farmer happened by and told Genwa that he would carefully dig up the tree the next day, so as not to damage any of its roots, and then have it delivered to his house.

“Oh, no, no!” exclaimed Genwa. I do not want that at all. Please allow it to remain exactly where it is.”

“Well, Master,” replied the farmer, “at least allow me to bring you the fruit from your tree when it is ripe.”

“Thank you for such an offer,” said Genwa. “However, I have no use for the fruit. Please take whatever fruit you desire and enjoy it yourself. To be quite honest, all that I desire is to enjoy the beauty of the flowers, and certainly, it would be most unfair to do that, if they belonged to someone else. And so, I bought them.”

Sunday, May 9, 2010

JAPANESE AESTHETICS: FURYU

Fūryū (風流)

The Japanese aesthetic Fūryū (風流) was derived from the Chinese word fengliu, which literally translated meant “good deportment” or “manners. After its “importation” to Japan in the eight century, the word came to refer more directly to the refined tastes of a cultivated person and to things what were associated with such people. When applied in a more aesthetic sense, the word fūryū took on a reference to the refined, even elegant behavior of an sophisticated person. As time went on, the word was applied to all things that were regarded as elegant, sophisticated, stylish, or artistic.

By the twelfth century, with the evolution of semantics in Japan, fūryū began to evolve into two distinct variations. The first variation applied fūryū to more earthy, ostentatious beauty as marked in popular art forms. In the second variation, people attempted to find fūryū in the beauty portrayed in landscape gardens, flower arrangements, architecture, and poetry about nature, normally written in classic Chinese. It was this second “branch” of fūryū that in part gave birth to cha-no-yu or the tea ceremony, during the Muromachi Jidai or Muromachi Era (1333- 1573).

During the Edo Period or Edo Jidai (1603 – 1868), a form of popular fūryū became evident through a style of fictional prose known as ukyo-zōshi.[i] A second popular interpretation of fūryū became apparent in such art forms as haikai[ii] poetry and the nanga[iii] style of painting; an interpretation that advocated a withdrawal from all of life’s burdens. An example of this version of fūryū may be found in the following poem by Bashō :

the beginning of fūryū

this rice planting

song of the north.

A more contemporary interpretation of fūryū, strongly influenced by Zen, lies in the two characters which comprise the term, 風流, wind and flowing. Just like the moving wind, fūryū can only be sensed: it cannot be seen. Fūryū is tangible yet at the same time, intangible in the elegance which it implies; moreover, just like the wind, fūryū puts forward a wordless, transitory beauty, which can be experienced only in the moment: in the next it is gone. Interestingly, several styles of folk dances, yayako odori and kaka odori, have come to be referred to as fūryū or “drifting on the wind” dances and are quite popular.

[i] Ukiyo-zōshi (浮世草子 ) or “books of the floating world” was the first major genus of popular Japanese fiction, by and large written between 1690 and 1770, primarily in Kyōto and Ōsaka. Ukiyo-zōshi style literature developed from kana-zōshi (仮名草子 ) [a type of printed Japanese book that was produced largely in Kyōto between 1600 and 1680, referring to books written in kana rather than kanji]. Indeed, ukiyo-zōshi was originally classified as kana-zōshi. The actual term ukiyo-zōshi first appeared around 1710, used in reference to romantic or erotic works; however, later the term came to refer to literature that included a diversity of subjects and aspects of life during the Edo Jidai. Life of a Sensuous Man, by Ihara Saikaku, is regarded as the first work of this type. The book, as well as other passionate literature, took its subject matter from writings of or about courtesans and guides to the pleasure quarters. Although Ihara’s works were not considered “high literature” at the time, they became extremely popular and were crucial to the further development and broadened appeal of the genre. After the 1770s, the style began to stagnate and to slowly decline.

[ii] Haikai (俳諧 , meaning comic or unorthodox) is short for haikai no renga, a popular style of Japanese linked verse that originate in the sixteenth century. Unlike the more aristocratic renga, haikai was regarded as a low style of linked verse intended primarily for the average person, the traveler, and for those who lived a less privileged lifestyle.

[iii] Nanga (南画 , or southern painting) also known and bunjinga (文人画 ) , intellectual painting) was a somewhat undefined school of Japanese painting which thrived during the late Edo Period. Its artists tended to regard themselves as an intellectual elite or literati. The artists who followed this school were both unique and independent; yet they all shared a high regard for traditional Chinese culture. Their paintings, most often rendered in black ink, but at times with light color, were inclined to represent Chinese landscapes or related subjects, much in the same form as Chinese wenrenhua or literati painting of the nanzonghua or Chinese “southern school” or art.

Copyright 2010 by Hayato Tokugawa and Shisei-Do Publications. All rights reserved.

Monday, January 18, 2010

JAPANESE AESTHETICS: Plants in the Visual Arts (Geijutsu to Shokubutsu)

The graphic or illustrative arts in Japan traditionally have relied on the sensitivity of the artist to nature and thus, have been likely to be simple, compact, and modest, yet elegant. Traditional renderings of landscapes, for example, do not display the wide range of colors that is seen in Western oil paintings or watercolors. This same simplicity and grace applies to sculpture as well: delicately carved and small in size.

Plants, flowers and birds, or at least their outlines are frequently rendered in lifelike colors on fabric, lacquer ware and ceramics. The love of natural forms and an enthusiasm for the expression of nature in idealized style have been the key intentions in the development of traditional Japanese arts such as ikebana (flower arrangement, chanoyou (the tea ceremony), tray landscapes (bonkei), bonsai, and landscape gardening. It is through these arts that the Japanese people have attempted to incorporate the beauty of nature into their spiritual values and daily lives.

For the decoration of a teahouse, a modest flower was selected to conform with the principle that flowers should always look as if they were still in nature. The Japanese have sought to express the immensity as well as the simplicity of nature with a single wild flower in a solitary vase.Tuesday, November 10, 2009

CHA-DO: It's Not Just For Ladies Anymore!

Even during the Meiji Era, the Era of Enlightened Rule, it was required, pre-marriage training for women. In the preceding Tokugawa Period, its study was encouraged among samurai and its practice the mark of a cultured gentleman. In the current Heisei Era, the time of Emperor Akihito it is becoming a much-sought out weapon in Japan’s war on stress. It is Cha-no-yu, Cha-Dō: the tea ceremony.

Throughout Japan, on any evening, and particularly on weekends, you may find Japanese men, business men, merchants, engineers, academics, gathered together in suburban tea houses, wearing kimono, hakama, and haori, to immerse themselves in traditional Japanese culture and in particular, this traditional Japanese art, as a means of shedding off the stress and strain of modern life. How? With what would be termed in the West as a “tea party.”

On any evening at the Urasenke School of Tea, one can find an ever increasing number of Japanese men studying the traditions and art of tea; indeed, on some evenings the number of male pupils (largely men over 40) outnumbers women. Japanese people, regardless of age or gender, are rediscovering the beauty and emotional calming effects of Cha-Dō, as a transcendental interlude, a time of peace and re-focusing one’s life. Numerous magazines have recently produced articles, even special “tea” editions, which were quickly sold out as Japan discovers that “new” is not always better and the old ways, tradition, can have a place of significance in the life of the modern Japanese man.

“Cha…it’s not just for ladies anymore!”

Friday, October 16, 2009

JAPANESE AESTHETICS (Bigaku)

JAPANESE AESTHETICS (Bigaku)

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of traditional Japanese aesthetic thought is the tendency to attach far greater value to symbolic depiction than realistic portrayals. Another attribute to be considered is the supposition that in order to be true art, a work has to involve a discerning representation of what is beautiful and an aversion from the crude and profane. As a result, artists have traditionally tended to select nature as their subject matter, steering clear of depictions of everyday, common life.

It was the Heian court, often described as having an exaggerated taste for grace and refinement, which exerted an enduring impact on subsequent cultural traditions, designating elegance as a key measure of beauty. Numerous cultural and artistic concepts, such as okashi, fūryū, yūgen, and iki carry with them a nuance of elegance.[1]

Another quality, one to which great value is attached, is impermanence or transience, itself a variation of elegance; exquisite beauty being regarded as both fragile and transitory. Metaphysical profoundness was provided through a merging of Buddhism, with its emphasis on the inconsistency and uncertainty of life, with this ideal. Numerous aesthetic conventions, such as wabi, sabi, yūgen and aware (with its subsequent amplification of mono no aware) all imply transience.

Over time, the presence of an artistically created void, in either time or space, became an important concept in aesthetic theory. The concept of simplicity became a culmination of the concepts of simulation and substitution, which stressed symbolic representation. Aesthetic concepts such as wabi, sabi, ma, shibui and yojō[2] are all inclined toward simplicity in terms of their basic inferences, consistently demonstrating distaste for elaborate beauty.

Simplicity denotes a certain naturalness or lack of pretense. In traditional Japanese aesthetics then, the separation between art and nature is considerably smaller than in Western art, stemming from the belief that the mysteries of nature cannot be presented through portrayal, but only suggested and the more succinct the suggestion, the more effective it becomes.

[1] The aesthetic concepts of wabi, sabi, yūgen, aware and mono no aware will be discussed in subsequent articles.

[2] The aesthetic concepts of ma, shibui, and yojō will be discussed in subsequent articles.

Saturday, December 27, 2008

THE SEA OFF SATTA by HIroshige

SAMURAI FIGHT

A riot - bands of samurai fighting in a snowy street in Edo as innocent citizens flee to safety.